Playback speed:

Living with neurodegenerative disorders like dementia does not mean individuals suddenly lose their functional capacity and work skills upon diagnosis. Unless it is rapidly progressive dementia, many of us continue to live well for a very long time if we do our part to stay physically fit, mentally active, socially engaged, and eat well.

However, there is one aspect of positive living that we need support and understanding from society. To us with young-onset dementia (YOD).

Receiving a “forced” retirement is the hardest blow.

Many diagnosed with YOD have to quit their jobs because of their cognitive decline, particularly in their executive function skills. There will be certain aspects of the functional capacities, which are no longer able to function at an optimal level. Skills like planning, time management, being organised, and multitasking are commonly affected by cognitive decline. While it does impact an individual’s productivity, efficiency, and effectiveness as a worker, the skills and experiences that they’ve acquired over the years can compensate for functional deterioration.

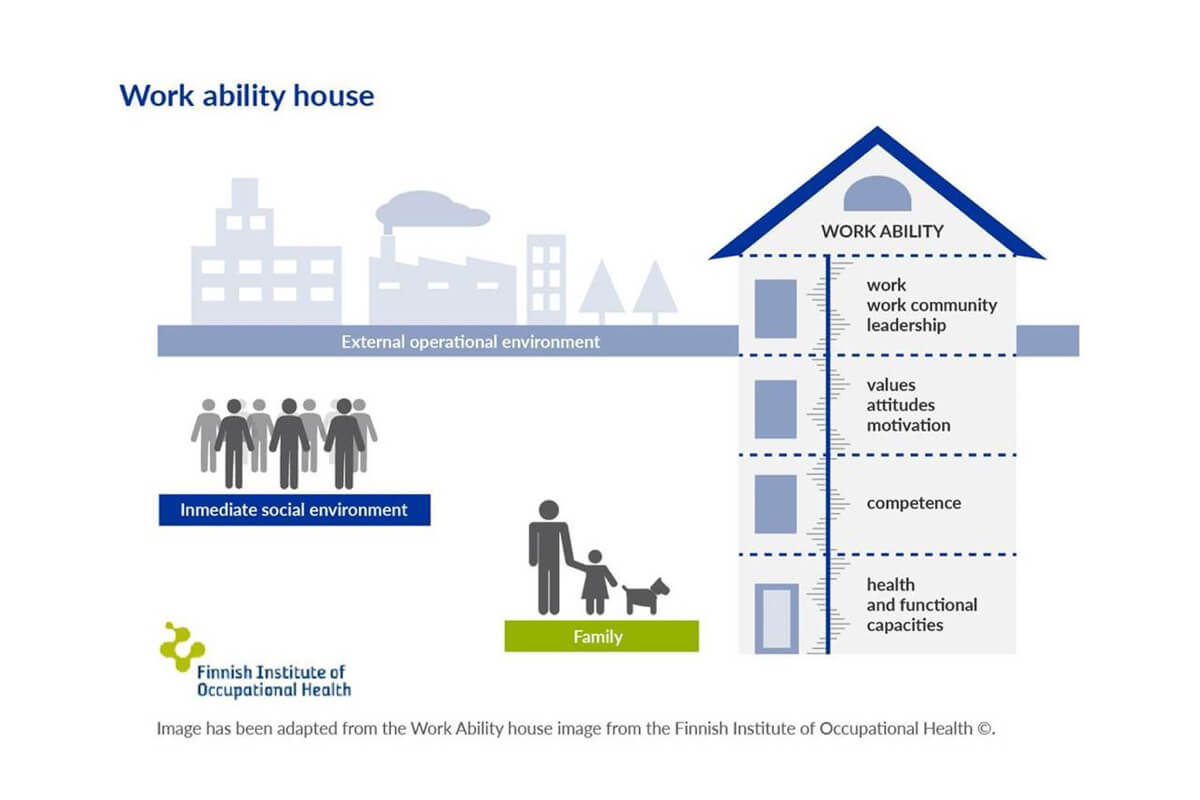

The term “workability” refers to the relationship between an individual’s resources and job scope. According to the work ability model by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, there are four interrelated tiers: with a base layer consisting of personal health and functional capacities; the next layer which is competence and skills; followed by the third layer which includes personal values, attitudes, and motivation; and the topmost layer is work, referring to work scope, work environment, organisation, and leadership.

Hence, it would be useful for any workplace to consider and decide the kind of work intervention needed to keep their employees living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or YOD. Beyond economic benefits, retaining the occupational role is vital to provide a sense of purpose in life and maintaining self-worth.

For this to work, the collaboration between the affected employee and the Human Resource Department is crucial. The employee has to feel safe enough to disclose the level of functional capacity without being discriminated against and judged.

The negative attitudes, which are often based on stereotypes and myths, include people with dementia who are unteachable and burdensome. Such perception can influence management decisions and implicates the employee’s situation.

With an inclusive work culture and willingness to support employees living with dementia to maintain their work skills, this is a feasible practice. It is also important for the government to formulate public health policies conducive to supporting those diagnosed with dementia at the workplace. This is especially necessary with the increasing number of cases of YOD over the years.

This commentary is in response to “Forum: Firms need to understand dementia better as the workforce ages” (The Straits Times, 19 January 2021) by Paul Heng, Management Committee Member at ADA

.

About Emily Ong

Emily was first diagnosed with neurodegenerative disorders at the age of 49, and provisionally diagnosed with Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) when she was 51. Emily has been a participant and co-facilitator of the Voices for Hope programme under Alzheimer’s Disease Association, and passionately advocates for a dementia enabling environment. Read more of her contributions here:

References

1. Keeping people with dementia or mild cognitive impairment in employment: A literature review on its determinants by Fabiola Silvaggi et al., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 29 January 2020.

This post was edited from the original post on the Dementia Singapore website.