Playback speed:

Participatory arts involve persons living with dementia and caregivers in their development, creation, and evaluation processes.

Introduction

Persons living with dementia gradually experience a decline in mental processes, including memory, orientation to space and time, and abstract thinking. The decline in cognitive skills may lead to social withdrawal and difficulties in communication.

To reduce this decline in cognitive and social skills, dementia specialists have expanded from the roots of biomedical treatment to explore other innovative interventions. They adopt the philosophy of ‘Re-mentia’, which refers to gradually improving the functioning of persons living with dementia by fostering a secure environment that sustains their well-being and remaining competencies. A specific non-pharmacological intervention that supports the notion of ‘Re-mentia’ is gaining increasing attention – participatory arts.

What Are Participatory Arts?

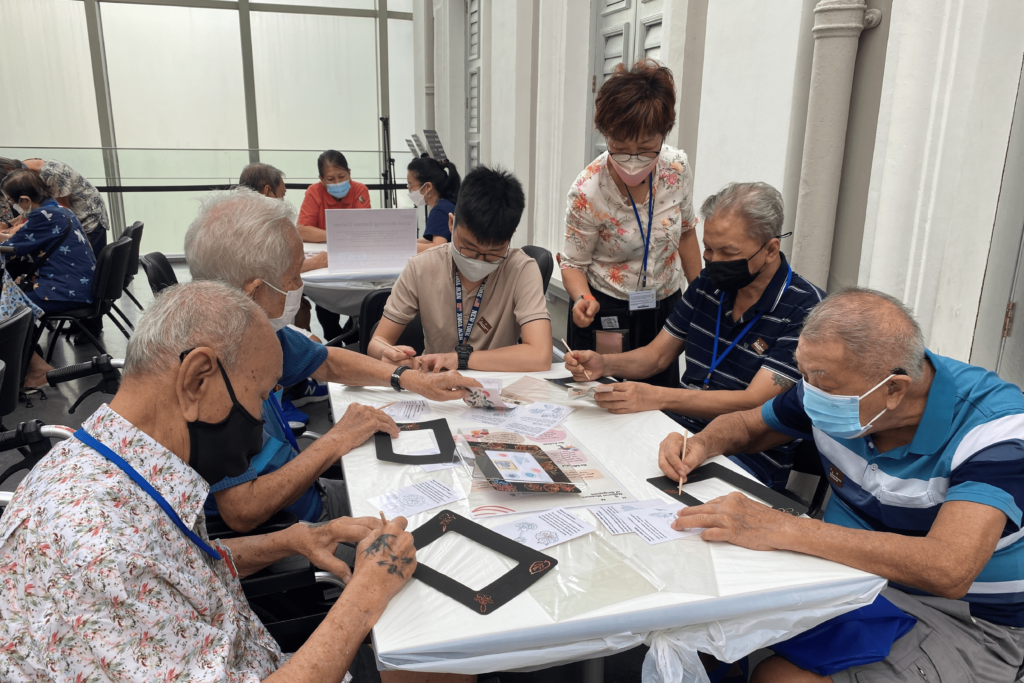

Participatory arts, also called community-based arts, constitute a range of activities that directly involve the participants in the development, creation, and evaluation processes. Activities involved may include conceptualizing ideas, experimenting with different mediums in the creative process, and exhibiting the final product to an audience.

Participatory art programs are often delivered over several weeks under the supervision of allied health professionals or art practitioners to small groups of participants and provide a failure-free space for creative expression, self-discovery, and social engagement. Some examples of these art forms include:

- Clay work, Pottery

- Craft work, Collage, Origami

- Expressive Writing, Poetry

- Music, Singing and Movement

- Performing Arts (Dance, Drama, Opera)

- Storytelling, Sharing life stories

- Visual Arts (Museums, Art Galleries)

Despite the variety of participatory arts available, they all share a common value base – person-centered care (PCC). The PCC approach comprises four components emphasized by program facilitators that promote individual dignity:

- Valuing persons living with dementia and their caretakers

- Understanding and tailoring to individualistic values, choices, and preferences

- Looking from the perspective of the individual

- Reinforcing a positive social environment

Participatory arts are art-related activities that involve persons living with dementia in the development, creation, and evaluation processes.

Benefits of Participatory Arts

By creating and building a space where persons living with dementia can feel safe and thrive, research suggests that engagement in these creative activities can enrich the lives of persons living with dementia. Synthesizing the findings across multiple research studies, the benefits can be summarized into these five fundamental aspects:

Nurturing a Purpose in Life

Promoting Autonomy

Enhancing Self-Esteem

Building Positive Relationships

Improving Cognitive Skills

Important Characteristics of Participatory Arts

Systematic research studies have highlighted the importance of several key aspects in the delivery of participatory arts programs that can maximize the likelihood of positive outcomes. These key aspects should ideally be integrated to construct a meaningful social and physical environment that promotes the well-being and remaining abilities of persons living with dementia.

Interacting Social Contexts

Organizing frequent and regular programs allows the strengthening of bonds among all participants involved in the program, including care partners and volunteers. Through the strengthening of bonds, facilitators build rapport and establish trust with persons living with dementia. This enables persons living with dementia to become accustomed to the program. Fostering a secure environment that allows everyone to interact with one another is foundational for instilling a sense of social inclusion and engagement.

Incorporation of Reminiscence

Exposure to the arts, especially those with significant cultural or historical value, can bring about unique topics of conversation among persons living with dementia. Through self-expression, persons with dementia can, in part, “re-live” their past in the stories they share through meaningful and structured discussions. The promotion of sharing experiences through self-expression and social engagement can serve as a catalyst for building a supportive and caring environment.

Incorporating Creativity and Imagination

The unique topics of conversation amongst persons living with dementia, facilitated by exposure to the arts, can encourage their creativity and imagination. It is pivotal to incorporate activities that tap on imagination and self-expression. These activities may include discussions about the cultural elements of viewing museum artifacts, or the practices of free association and story-sharing through reminiscing with music or images.

Role of the Facilitator

The facilitator’s role includes encouraging interactions among participants, imparting knowledge, and serving as a role model of confidence and love for learning. Through framing challenges for participants to tackle, promoting self-exploration and discovery, and validating participants’ artwork, facilitators can build an intellectually and socially stimulating environment for everyone to challenge their own abilities and learn from each another.

Beyond Individuals With Dementia – Advocacy for an Inclusive Society

A pressing concern in society today is the social stigma towards persons living with age-related conditions, including dementia. As a result of the stigma, these individuals may experience negative emotions, self-discrimination, and poor self-efficacy.

In recognition of the importance of reducing discrimination and stigma towards persons living with dementia, contemporary societal movements have been initiated and have witnessed benefits.

Dementia-Friendly Communities (DFC) adopt the PCC approach and employ participatory art activities to connect persons living with dementia with members of the public. Social prescribing interventions, such as the “Arts on Prescription” model, reflect the validation and importance of a holistic approach to well-being.

Frequent interactions between members of the public and persons living with dementia can promote greater understanding of dementia and a more positive attitude towards this condition.

With the knowledge that stigma is often propagated by misconceptions, lack of knowledge, and the absence of one-on-one interaction with stigmatized populations, these movements aim to provide opportunities for members of the public to personally interact with community members who are experiencing dementia. Frequent interactions between members of the public and persons living with dementia can promote greater understanding of dementia and a more positive attitude towards this condition. Fostering care and acceptance in the community towards persons living with dementia can encourage these persons to learn to strive, and maintain meaningful, independent lives.

Here are some participatory arts programs for persons living with dementia:

Sing Out Loud!

Sing Out Loud! was developed by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay in partnership with Dementia Singapore in 2016. This programme is built on the belief that the arts is transformative and can be used to promote positive ageing, boost mental wellness, and enhance overall well-being in persons living with dementia, and their caregivers.

It offers a nurturing platform for participants to learn new vocal techniques and helps stimulate emotional and memory recall through the reminiscence of songs, culminating in a graduation showcase at the end of the eight-week programme. Each session is low in intensity, making it especially suitable for persons with dementia. It consists of eight vocal sessions stretched over two to four months, and may also include learning simple choreography.

The programme is tailored to suit different levels of physical mobility and participants’ needs, and is facilitated by artists, with inputs from therapists and social service professionals. Participants learn voice projection, breathing techniques, use of the diaphragm as well as facial muscles to control tone and pitch.

Art With You

Art With You is an evidence-based museum programme developed by National Gallery Singapore (NGS) in partnership with Dementia Singapore (DSG). It combines people-centred care with arts engagement, and aims to foster positive and meaningful engagement that supports the wellbeing of caregivers and persons with dementia.

Participants may choose between guided group visits led by the docents at NGS or self-guided visits where they can enjoy the Gallery at their leisure using the Art with You Caregivers Guide and Art Kit (art-making materials).

For more information on ticketing and concessions, please visit https://www.nationalgallery.sg/admissions.

Reunion

Source: National Museum of Singapore

Reunion is a dedicated social space in the National Museum of Singapore for seniors, including those living with mild cognitive impairment and dementia, to engage in meaningful activities and conversations inspired by museum artefacts.

Reunion has two main areas – a space for various individual and group activities as well as a café. The all-inclusive activity space features a designated area for group activities, music booths, an immersive projective cave and a Quiet Room.

- Group activities

There are handling objects and conversation starter guides featuring the museum’s National Collection that are located around the Reunion space. Visitors are encouraged to pick them up for use and engage in reminiscence conversations with others. There are also other kinds of activities such as monthly workshops and Quiet Morning Drop-ins which allow visitors to explore the museum’s collection and stories through hands-on activities featuring different art forms. - Music booth

Persons living with dementia and their caregivers can select familiar tunes on an easy-to-navigate display panel. - Immersive projective cave

Also known as Memory Lane, this section of the space allows visitors to create their own digital exhibitions and view virtual exhibitions designed by past participants. - Quiet Room

This room serves as a safe space for visitors who might experience sensory overload and need a private and relaxing environment to decompress before resuming their museum visit.

The café, known as Café Brera, is a perfect spot for hearty conversations with family and friends. It also serves dysphagia-friendly food, which is suitable for those with swallowing difficulties.

For more information about programmes for seniors that are held at Reunion, please visit https://go.gov.sg/reunionprogs.

The Future of Participatory Arts

As participatory arts are progressively implemented in dementia care settings, there may be a lack of facilitators available to guide small-group programs. With the advancement of technology, virtual reality (VR) technology may provide a cost-effective, accessible, and flexible method to address these human resource concerns by providing an alternative interactive platform for persons living with dementia to engage in the arts.

VR refers to a computer-generated artificial environment, which individuals can freely interact with using body tracking devices and visual displays. Recently, research exploring customized VR designs for persons living with dementia suggests that VR can provide a secure, pleasant, and evocative environment for individuals to interact with. Some VR-facilitated activities include visiting virtual locations (e.g. a countryside, beach, or forest) of one’s choosing, multi-sensory relaxation exercises, and virtual museums or art gallery tours. These VR capabilities facilitate a larger goal of VR technology implementation, which is to provide persons living with dementia an opportunity to engage in life that otherwise might not be possible due to their health or mobility limitations.

The emerging research on the implementation of VR technology in dementia care is promising. More insights, particularly in design factors for optimal user experience and the personalization of VR technology to improving cognitive skills is an ongoing area of active experimentation and implementation.

Conclusion

As their memory and communication skills decline, the opportunities for persons living with dementia to have meaningful interactions with their loved ones can become increasingly scarce. ‘Re-menting’ interventions, such as bringing art-based programs to persons living with dementia, offer soulful and refreshing experiences and bring about opportunities for persons living with dementia to forge closer relationships with their care partners and interact with the society.

Tell us how we can improve?

Read Next

Reminiscence in Dementia Care

Reminiscence is a method in dementia care that focuses on facilitating recollection about past events and experiences with persons living with dementia. This recollection

Psychosocial Interventions in Dementia Care

Psychosocial interventions is an umbrella term for a wide range of non-pharmacological interventions, activities, therapies, strategies, etc. that aim to promote the psychological and

Creative Dance

Dancing can be a form of expression for persons living with dementia too, as they connect and interact with others through dance. Read on

- Allen‐Burge, R., Stevens, A. B., & Burgio, L. D. (1999). Effective behavioral interventions for decreasing dementia‐related challenging behavior in nursing homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(3), 213-228.

- Alluri, V., Toiviainen, P., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Glerean, E., Sams, M., & Brattico, E. (2012). Large-scale brain networks emerge from dynamic processing of musical timbre, key and rhythm. Neuroimage, 59, 3677– 3689. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.019

- Brooker, D. (2003). What is person-centred care in dementia?. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13(3), 215-222. doi:10.1017/S095925980400108X

- Bungay, H., & Clift, S. (2010). Arts on prescription: a review of practice in the UK. Perspectives in Public Health, 130(6), 277-281. doi:10.1177/1757913910384050

- Corrigan, P. W. (2007). How clinical diagnosis might exacerbate the stigma of mental illness. Social Work, 52(1), 31-39. doi:10.1093/sw/52.1.31.

- Creech, A., Hallam, S., McQueen, H., & Varvarigou, M. (2013). The power of music in the lives of older adults. Research Studies in Music Education, 35(1), 87-102. doi:10.1177/1321103X13478862

- Crocker, J. (1999). Social stigma and self-esteem: Situational construction of self-worth. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 89-107. doi:10.1006/jesp.1998.1369

- Difede, J., Cukor, J., Patt, I., Giosan, C., & Hoffman, H. (2006). The application of virtual reality to the treatment of PTSD following the WTC attack. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 500-501. doi:10.1196/annals.1364.052

- Douglas, S., James, I., & Ballard, C. (2004). Non-pharmacological interventions in dementia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 10, 171-179. doi:10.1192/apt.10.3.171

- Garcia-Betances, R. I., Jiménez-Mixco, V., Arredondo, M. T., & Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M. F. (2015). Using virtual reality for cognitive training of the elderly. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 30(1), 49-54. doi:10.1177/1533317514545866

- Hebert, C. A., & Scales, K. (2019). Dementia Friendly Initiatives: A State of the Science Review. Dementia, 18(5), 1858-1895. doi:10.1177/1471301217731433

- Hodge, J., Balaam, M., Hastings, S., & Morrissey, K. (2018, April). Exploring the design of tailored virtual reality experiences for people with dementia. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-13).

- Janata, P. (2009). The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 2579–2594. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp008

- Janata, P., Tillmann, B., & Bharucha, J. J. (2002). Listening to polyphonic music recruits domain-general attention and working memory circuits. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 2, 121–140. doi:10.3758/CABN.2.2.121

- Kim, O., Pang, Y., & Kim, J. H. (2019). The effectiveness of virtual reality for people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 219. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2180-x

- Poulos, R. G., Marwood, S., Harkin, D., Opher, S., Clift, S., Cole, A. M., … & Poulos, C. J. (2019). Arts on prescription for community‐dwelling older people with a range of health and wellness needs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(2), 483-492. doi:10.1111/hsc.12669

- Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M., Laitinen, S., Numminen, A., Kurki, M., Johnson, J. K., & Rantanen, P. (2014). Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. The Gerontologist, 54(4), 634-650. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt100

- Sixsmith, A., Stilwell, J., & Copeland, J. (1993). ‘Rementia’: Challenging the limits of dementia care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 8(12), 993-1000. doi:10.1002/gps.930081205

- Stevens, A.B., & Burgio, L.D. (1999). Effective behavioural interventions for decreasing dementia-related challenging behaviour in nursing homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(3), 217-228. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199903)14:3<213::AID-GPS974>3.0.CO;2-0

- Stuart, H. (2006). Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments. CNS Drugs, 20(2), 99-106. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002

- Tarr, M. J., & Warren, W. H. (2002). Virtual reality in behavioral neuroscience and beyond. Nature Neuroscience, 5(11), 1089-1092. doi:10.1038/nn948

- Taylor, A., & Hallam, S. (2008). Understanding what it means for older students to learn basic musical skills on a keyboard instrument. Music Education Research, 10(2), 285-306. doi:10.1080/14613800802079148

- Thompson, R. (2015). Transforming dementia care in acute hospitals. Nursing Standard, 30(3), 43. doi:10.7748/ns.30.3.43.e9794

- Thomson, L. J., Lockyer, B., Camic, P. M., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2018). Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(1), 28-38. doi:10.1177/1757913917737563

- Todd, C., Camic, P. M., Lockyer, B., Thomson, L. J., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2017). Museum-based programs for socially isolated older adults: understanding what works. Health & Place, 48, 47-55. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.08.005

- Weersing, V. R., & Weisz, J. R. (2002). Community clinic treatment of depressed youth: benchmarking usual care against CBT clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 299. doi:10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.299

- World Health Organization. (2014). Basic documents (49th Edn). Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-en.pdf

- Young, R., Camic, P. M., & Tischler, V. (2016). The impact of community-based arts and health interventions on cognition in people with dementia: A systematic literature review. Aging & Mental Health, 20(4), 337-351. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1011080