Alzheimer’s Disease is the most well-know and researched type of dementia, caused by changes at the cellular level in the neocortex. We offer a general explanation of the causes, symptoms, prevalence and risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

What is Alzheimer's Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for an estimated 60-80% of all dementia diagnoses 1. It is a progressive neurocognitive disease, which means symptoms gradually worsen over a long period of time barring the presence of other health conditions. It progresses slowly because brain changes occur at the cellular level and accumulate with age. The key sign of Alzheimer’s disease is the abnormal build-up of amyloid-beta proteins around the neurons in the brain.

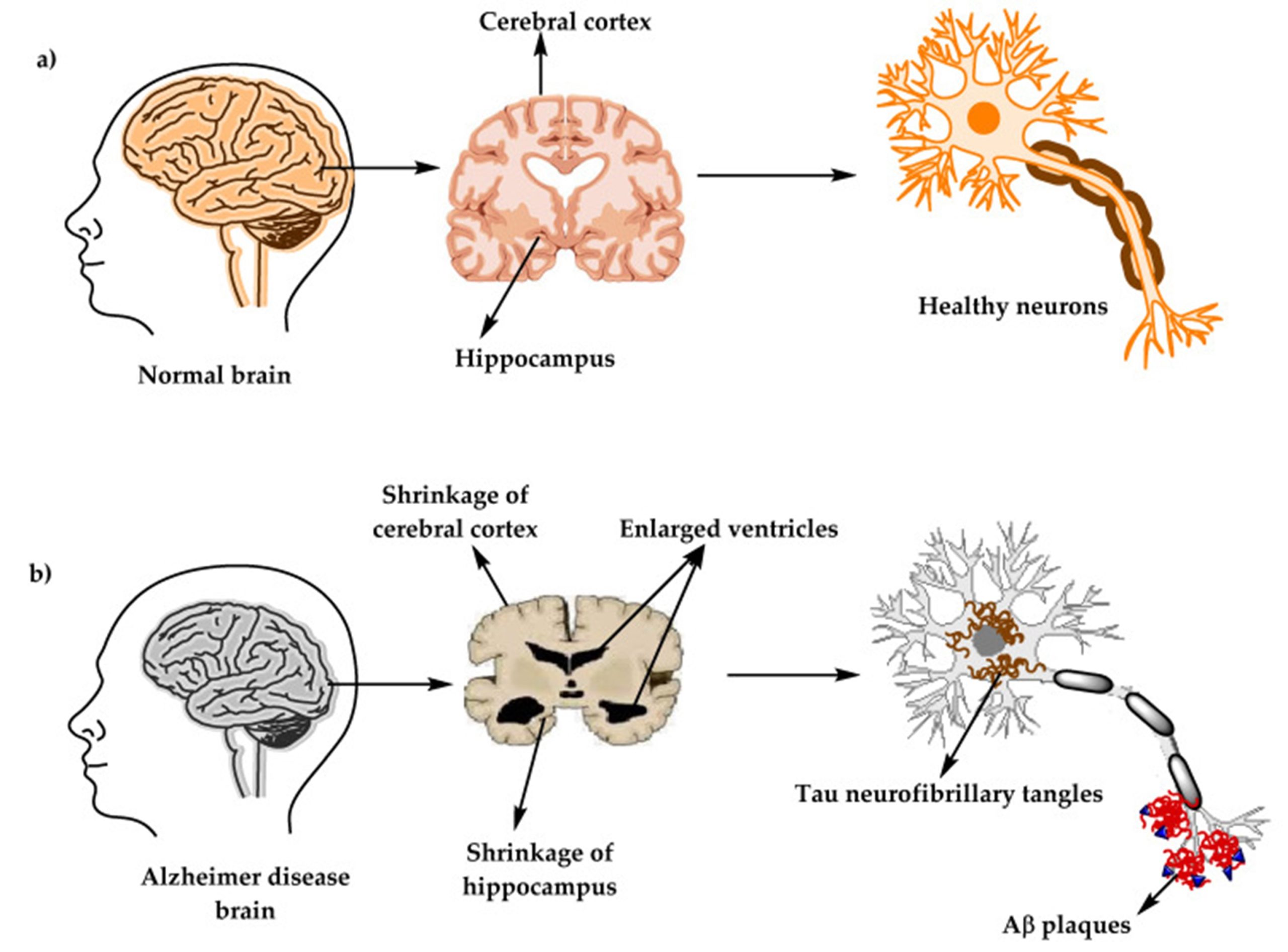

(Image: Structure of a healthy brain versus a brain observed in Alzheimer’s disease, adapted from Brejyeh and Karaman, 2020)

Normally, these proteins are disposed of as waste, but this process requires the proper involvement of three enzymes (α-, β- and γ-secretase) that cut the proteins. When either of these enzymes show abnormal activity, the beta-amyloid proteins accumulate around the outside of neurons, forming plaques that interfere with communication between neurons. This eventually leads to the cell death of neurons and shrinkage of cortex (brain tissue), in areas needed for language, memory and planning.

Another common explanation is the formation of tangles within the neuron cells composed of tau protein. These tangles are known as neurofibrillary tangles, and although both are considered biomarkers that indicate whether a person has Alzheimer’s disease, scattered amyloid protein plaques can be found commonly in brains of older persons who do not have Alzheimer’s disease. Neuritic plaques where the amyloid protein is more densely packed among neurites that have been distorted by neurofibrillary tangles are considered to be a more specific marker for Alzheimer’s disease.

How Common is Alzheimer's Disease?

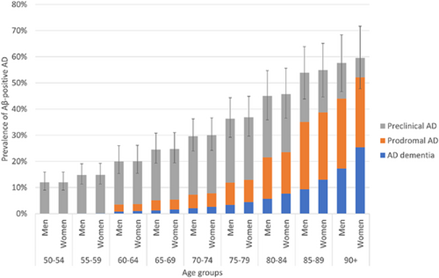

Figure: Global prevalence of amyloid-beta related AD by age, adapted from Gustavsson et. al)

Excluding those with symptom severity milder than the benchmark for formal diagnosis (pre-clinical AD), it is estimated that around 32 million people have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease globally3.

Age is the most important factor in prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease. The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease roughly doubles with every 5 years’ increase in age beyond the age of 65. It is estimated that at least 25% of persons aged 85 and older have Alzheimer’s disease.

Even accounting for gender-related differences in lifespan, women have a higher frequency of Alzheimer’s disease than men.2

Main Symptoms of Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s disease causes progressive functional and cognitive impairment. Typically, early in the course of a disease, a person undergoes a phase called a pre-clinical stage where symptoms have yet to show or are too mild a person experiences mild memory loss but may not show functional impairment in daily activities.

In the mild stage, the person may experience difficulty concentrating and remembering things. They might also be disoriented to place and time and experience mood fluctuations or depressed mood.

In moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, the person experiences increased memory loss and may have difficulty recognizing family and friends. Their impulse control, reading, writing and speech may be affected. Eventually, they may become bedridden when brain areas for motor function are impacted and have difficulties with swallowing and urination.

When symptoms are developed before the age of 65, the person is said to have early-onset AD. Most cases are diagnosed after the age of 65, which is known as late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. In late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, structural changes in the cortex and hippocampus (brain area responsible for memory) can be observed with only mild cognitive impairment. At this stage, symptoms can be managed and even recovered from, which is why early screening for Alzheimer’s disease can greatly affect prognosis.

A person can also develop mixed dementia, which happens when a person has more than one type of dementia. Most cases of mixed dementia happen with Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia since they are the two most common types of dementia. Persons with mixed dementia will show signs of both types of dementia, with one type of dementia often being predominant.

Genetic Risk for Alzheimer's Disease

In comparison to late-onset AD, early onset AD is more likely caused by inherited genetic risk factors for the disease. This means that if someone you are biologically related to has early-onset AD, you may have a higher likelihood to develop the condition. When one is screened for genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease, they are screened for:

- Mutations in the genes coding for proteins that eventually form amyloid-beta proteins.

- Mutations in the proteins that control the activity of secretase enzymes involved in the disposal of amyloid protein.

Cholesterol levels near the cell membrane of neurons also affect the activity of the secretase enzymes. High cholesterol levels imbalance the lipid metabolism system (the storage and digestion of fats) in neurons, encouraging quicker formation of amyloid plaques. Because of this, a protein inside neurons called apolipoprotein E (ApoE) which is involved in lipid metabolism is also actively studied by researchers in its relation to Alzheimer’s disease risk. There are several forms of this protein, but most of us have a gene for one of its three common forms. Persons who possess the ApoE2 gene are thought to have a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, while those with the ApoE4 gene have a higher overall risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease whether early or late-onset.

It must be noted that having these particular genes increases one’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease but does not guarantee the development of the disease. Such genetic tests help advise individuals at risk to make lifestyle changes to manage their risk of Alzheimer’s disease. These genetic risk factors influence the development of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, but there are over 20 genes that seem to have an additive effect on one’s risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Managing Risk

Because Alzheimer’s disease is linked to lipid metabolism, many chronic health conditions like obesity, hypertension and dislipidemias are also linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Hence, one’s lifestyle habits can increase one’s risk of the disease. This includes:

- Insufficient exercise

- Frequent or over-consumption of alcohol

- Smoking

- Having a high-fat or high-sugar diet

- Insufficient sleep

Apart from lifestyle and genetic factors, head injury and environmental factors like air pollution and heavy metal exposure can also increase one’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease. You can read more about managing risk for Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia here.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis process often starts with a review of the person’s medical history and observed cognitive and behavioural changes. The doctor will likely ask about medications the person is taking and whether other family members have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The person may be requested to take cognitive, functional and behavioural tests like the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to determine if cognitive and behavioural symptoms are cause for concern; and whether they significantly impair daily function.

This is often followed by brain imaging scans like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). This allows the doctor to assess whether structural changes like shrinkage of the cortex have occurred which support the diagnosis, or whether the person has other conditions that can cause similar symptoms to those with Alzheimer’s disease, such as a stroke or brain tumours.

Additional tests, including cerebrospinal fluid and blood tests, may also be carried out to check for abnormal protein levels, such as amyloid-beta or tau, which are linked to AD.

For more information on the full diagnosis process, read this article.

How can I get support for myself or a loved one?

If you are concerned that someone you know or yourself may be at risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, you can approach your GP (General Practitioner) or family doctor for a referral or encourage them to seek a diagnosis. Find out more on diagnosis through :

You can also contact a Community Outreach Team (CREST). To get support, call Dementia Singapore’s helpline at 6377 0700.

Video: I Was An SAF Commando. Alzheimer’s Won’t Stop The Fighter In Me

Source: CNA Insider

Ex-Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) officer Peter Estrop was diagnosed with one of the most common types of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, at 61. The former commando experiences cognitive decline which affects his memory. In this video, he and his wife Evon talk about how they have adapted to living with dementia after the diagnosis.

Additional Resources

Understanding Different Types of Dementia (PDF)

Source: National Institute on Aging

This poster summarises the four most common types of dementia by their characteristics and differences.

Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: what everyone needs to know by Sabat, Steven R.

Available for loan from the National Library Board

In this guide, Sabat outlines the definition and symptoms of dementia as a disease, how it can change the life (including subjective experience, emotional well-being and social life) of a person with dementia, the biological aspects of dementia, how it is diagnosed, and what care partners can do to maintain a positive relationship with the person living with dementia.

Tell us how we can improve?

Read Next

- Alzheimer’s Association. What is Alzheimer’s Disease? (2024, November 10.)

- Breijyeh, Z., & Karaman, R. (2020). Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(24), 5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245789

- Gustavsson A, Norton N, Fast T, et al. Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023; 19: 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12694

Alzheimer’s Disease. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences p. 91-96. Editors: Robert B. Daroff, Michael J. Aminoff Schachter AS, Davis KL. Alzheimer’s disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2000 Jun;2(2):91-100.

Villamil-Ortiz, B.J.L. Eggen, G.P. Cardona-Gόmez, Chapter 26 – Lipids, beta-secretase 1, and Alzheimer disease. Editor(s): Colin R. Martin, Victor R. Preedy, Rajkumar Rajendram, Factors Affecting Neurological Aging, Academic Press, 2021, Pages 289-299.

- The Straits Times. Blood test could detect Alzheimer’s years before symptoms occur (2022, December 6). https://www.straitstimes.com/world/united-states/blood-test-could-detect-alzheimer-s-years-before-symptoms-occur